Entries by Chris (169)

ARGO by DigiLens

Monday, January 6, 2025 at 9:45PM

Monday, January 6, 2025 at 9:45PM

In this article I make two arguments:

❶ If your company has been implementing an enterprise or industrial AR solution on HoloLens or MagicLeap and you’re now wondering where to go—especially if your work environment requires a ruggedized device—you should be looking at ARGO by DigiLens. We will explore use cases.

❷ The cancellation of the HoloLens has thrown Microsoft’s military contract for IVAS (Integrated Visual Augmentation System) into limbo. Microsoft is exploring a military-only option that remains up in the air, and have also brought in Anduril as a partner.

Some business narrative is also included…

There is a strong case for migrating to DigiLens’ ARGO for the U.S. military’s IVAS platform, and if ARGO is a ruggedized solution, solid enough for the U.S. military, enterprise and industrial users will find that it exceeds their expectations.

ARGO is DigiLens’ standalone AR smart glasses platform, designed for enterprise and industrial workflows. It is the preeminent ruggedized stereoscopic smart glasses platform available, and on the market, now.

DigiLens is an American company, based in Sunnyvale, CA. They are not newcomers. Founded over twenty years ago, DigiLens has weathered the storms that have seen other competitors come and go. Their core technology has always been display tech.

I demoed ARGO earlier this year at AWE 2024 Long Beach. I had previous demoed DigiLens’ Crystal30 display used in the ARGO glasses, and did not need to be further sold on the quality of their waveguides, but the platform as a whole is much more than just DigiLens’ world class display technology.

To demonstrate ARGO’s rugged design, the DigiLens team member slammed them to the floor—he did not drop them, I reiterate, he slammed them to the ground. Their booth did have some low-pile commercial carpeting… but still. He then gave them a smack on the counter, before tossing them tumbling across its hard surface. Impressive enough once, but perhaps the greater testament to their durability was that he and his DigiLens colleagues performed such demonstrations on the ARGO for three days, showing a high level of confidence in ARGO’s resilience.

In the military’s assessment of Microsoft HoloLens for use in the last iteration of IVAS, perhaps their most damning evaluation was HoloLens’ lack of ruggedness—HoloLens was deemed too fragile for the battlefield. There is no other more rugged headset / smart glasses on the market than ARGO.

ARGO is also modular.

One among many incremental improvements, the U.S. Army had Microsoft produce a “flip-up display” version of HoloLens, and such a feature is a mandatory for consideration for the IVAS system. DigiLens’ ARGO has removable ear-horns, revealing hinge connectors that attaches to ARGO’s own HALO branded visor peripheral. With ARGO’s modular platform, the hinge connectors can easily be adapted for a helmet.

The HALO visor accommodates for enough space, for those who wish to use the ARGO with their own prescription lenses. If however the wearer wishes, corrective lens can be ordered, that snap into ARGO itself, via a partnership with Frame of Choice.

I approached DigiLens about this article, and was alerted to a pre-existing relationship with Microsoft, an important partner of theirs. I suggest that this is a good thing. Ultimately Microsoft is a software company who is discontinuing their own commercial AR hardware platform. DigiLens is a hardware manufacturer with a core competency in near-eye display technology. DigiLens does not have the scale that Microsoft has to deliver on software solutions. If Microsoft is getting out of the AR headset business, DigiLens won’t be competing with them when being considered for IVAS, rather they can be the Army’s hardware solution, leaving each to focus on what they do best.

DigiLens already holds an Authority to Operate (ATO) with the U.S. military, enabling its technology to be deployed in military environments; and ARGO has ATAK integration, making it plug-and-play for military deployment.

We’re going to get to use cases — both military, and industrial — in a moment, but I’m going to insert an anecdote of my own here, that inspired this ARGO review:

|

||

|

|

In 2018, I relocated from the Bay Area back to New York City (for unrelated personal reasons), where a friend had recently joined United Technologies Digital (UTD). At the time their parent company United Technologies (UT)—a conglomerate serving architectural-engineering and aerospace markets—was in the process of acquiring RockwellCollins, and facing pressure from activist investors to break up the company, led by Bill Ackman of Pershing Square Capital. CEO Gregory Hayes opposed the breakup insisting synergies could be leveraged between these otherwise disparate markets. UTD was created partly as a commitment to pursuing these synergies, functioning as a software subsidiary with internal UT clients, as well as an accelerator connecting UT with NYC’s startup scene.

My pitch to UTD was to use Rockwell’s IDVS AR headset for industrial applications across other UT business units. In addition to showcasing further synergy—supporting Hayes’ case to the shareholders—it could also generate internal revenue for UTD, as specialized software would need to be developed for each deployment. Initially, I had focused on Otis Elevator, as there was, and remains, a widespread shortage of tradesmen for elevator installation and maintenance (more on this later). However, UTD’s most active internal clients were Pratt & Whitney and Carrier HVAC. UTD management also noted a general lack of knowledge about augmented reality within the company. Hence, my executive presentation grew to include an educational overview of AR, including a primer on waveguide technology; an overview of Rockwell’s IDVS device (highlighting related IP, jointly held with DigiLens); culminating with two competitive case studies: one implementing an AR headset that boosted productivity in jet engine assembly at GE, to make the case for Pratt & Whitney; and the other using an AR headset for quality control and optimization in commercial HVAC installation by Mortenson, making the case for Carrier. The intention had been to coordinate the presentation for when Gary Hayes and other members of management, based up in Connecticut, would be in New York City. While this timing did not work, interest in the presentation grew internally, so we moved it to the company lecture hall where all employees were invited, while Hayes and other members of management in Connecticut would join via video stream, which was then made available company wide. Though the presentation was well-received, management did not move forward with an engagement—I was given warm intros to virtually all their subsidiaries (including Rockwell), but regulatory scrutiny over the acquisition and uncertainty surrounding a potential breakup put any new outside engagements on hold. A few weeks later, in November of 2018… On November 26, United Technologies Corp. announced the completion of their acquisition of RockwellCollins. On the same day, they also announced the breakup of the conglomerate (Bill Ackman won), spinning off their architectural engineering holdings. Two days later on November 28, the U.S. Army awarded Microsoft a contract to develop the Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) using their HoloLens AR headset. I have no source suggesting that the later was a direct result of the former, but awarding the IVAS platform to Microsoft did move the U.S. military’s research and investment in AR headsets for the battlefield from RockwellCollins’ IDVS to Microsoft and the IVAS platform… and if I had been at Microsoft, I certainly would have seen this as a window of opportunity. We’ll recap the progress of all of this M&A at the end of this article, but for now… |

|

Let’s get back to DigiLens ARGO…

Oak Ridge, Tennessee, carries a unique legacy. Born from the urgency of the Manhattan Project, Oak Ridge National Laboratory played a pivotal role in the development of the atomic bomb. This historical context provides the crucial backdrop for understanding the mission of the Oak Ridge Enhanced Technology and Training Center (ORETTC). While ORNL continues to push the boundaries of scientific discovery, ORETTC focuses on a critical and evolving challenge: preparing first responders to effectively handle high-consequence radiological and nuclear material response scenarios. Building upon the region’s historical expertise in nuclear science and technology, ORETTC leverages this legacy to train and equip emergency personnel with the knowledge and skills necessary to safeguard communities and mitigate potential threats.

Launched in January, 2023, the Oak Ridge Enhanced Technology and Training Center (ORETTC) is leveraging augmented reality (AR) to modernize training and operational capabilities. In collaboration with DigiLens and their ARGO smart glasses, the ORETTC integrates spatial computing to enhance efficiency, safety, and training outcomes for first responders and nuclear operations professionals, including real-time data visualization, remote expert guidance, and hands-free operation in complex and hazardous scenarios, thus improving decision-making and operational precision in the field.

The U.S. labor market faces significant shortages of skilled tradesmen. Since my aforementioned proposal to UT for OTIS elevator servicemen, this has not change. It has not changed for elevator service technicians, nor has it changed for virtually any and all tradesmen in the U.S. labor market.

Today, however, there is a mature software product that addresses this problem.

Where my past proposal to OTIS/UT involved UTD developing their own software in-house, Manifest by Taqtile is an off-the-shelf product that is the state of the art in AR, for enterprise scale instructional content, for both military and industrial applications.

Manifest by Taqtile is the preeminent professional-grade AR software for heads-up and hands-free training and maintenance, manufacturing, and inspection, with spatially anchored content & remote assistance.

Training a new generation of tradesman is mission critical for American success.

With the launch of ARGO in January 2023, it was announced by May that DigiLens and Taqtile would be collaborating to port Manifest to the ARGO platform. The ARGO native version of Manifest launched in June of 2024.

Of the major AR headsets used in the field: Manifest launched on Microsoft HoloLens in 2017. Manifest launched on MagicLeap in 2018. Manifest launched on Apple Vision Pro in 2024.

In October 2024, Microsoft discontinued HoloLens. MagicLeap discontinued their headset last month, and Apple killed the Vision Pro the same month Manifest was ported.

A stand-alone device, ARGO is the most rugged AR headset / smart glasses device on the market. If you want to deploy Taqtile’s Manifest software on a smart glasses device suitable for industrial environments, available and shipping now, ARGO is the only real choice.

The Taqtile website has an exceptional library of use cases for businesses already using their product in the field, and on the factory floor. A combination of spatially anchored instructional content, augmented with remote assistance pulled from a company’s near retirement workforce will be able train a new tradesmen workforce, as well as digitally capture a company’s institutional memory from their most seasoned tradesmen.

Manifest also has a companion product, Manifest Maker—an Apple iOS based, no-code developer environment, that employs AI to transcribe and segment existing or new videos into step-by-step text instructions that can be augmented with images, text notes, PDFs, and video clips.Download Taqtile Manifest Maker from the Apple App Store. Play with it. See how easy it is. Publish to Manifest… then go get your ARGOs.

The evolution of drones has been to imbue them with intelligence, and grant them a great deal more autonomy. Assign a goal, or a role on the team, to a coordinated group on devices and grant them the independence to make the intermediary decisions in executing that assignment. The best UI for communicating with these digital team members will not be a traditional remote control.

In the existing user interface (UI), a proprietary device for both controlling the drone, and viewing through its camera(s) on a screen on that device, is also going to evolve. Just as the smartphone ate most all formerly single-purposes devices, smart glasses are going to eat many single purpose controllers as well. Given that a drone’s controller is a cumbersome extra piece of equipment to lug around, and requires both hands to operate, puts a soldier in a vulnerable position, in a high-risk environment where a distraction can be a matter of life and death.

Skydio’s autonomous capabilities are the industry standard. With its sophisticated obstacle avoidance algorithm and follow feature, it needs little attention beyond setting its objective, even in dynamic environments. Heads-up and hands-free, the soldier is now unencumbered, can administer multiple drones at once—a forward scout, a high-flying aerial drone with a wide field-of-view over the territory, and third flying close behind, who has his back. With ARGO, the soldier can summon the view from any camera, on any device, at any time, without putting down his weapon. In this manner, the combination of autonomous robotic agents gives the soldier total situational awareness.

The combination of ARGO, and autonomous agents, is a true force multiplier.

The arguments against automation made by the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), the union representing dockworkers at major U.S. East Coast ports, is principally driven by fear of job displacement, and economic survival of their union members.

It is often states that AI is not going to take your job, another worker who is using AI is going to take your job.

The busiest port represented by the ILA is the Port of New York and New Jersey, moving approximately 124 million short tons of cargo, annually. By comparison, the automated Port of Shanghai moves about 777 million short tons. The Port of Shanghai currently moves more than six-times the volume of the Port of New York and New Jersey.

Most of that cargo is coming from China, the bulk transverses the Panama Canal, over to the U.S. East Coast though some cross the Indian Ocean, and come through the Suez Canal, and across the Atlantic. Based on 2023’s data, the Port of New York and New Jersey employ approximately 8,345 people. By comparison, the Port of Shanghai reported having 13,036 employees by end of 2023.

While high-volume automated Chinese ports may employ many more people, the style of automation adopted in China is one largely operated by desk-workers in control centers, monitoring and managing operations remotely via computer screens.

It is my belief that a significant part of the resistance to automation by American Longshoremen is not just about automating away job security, but rather, the obliteration of their masculine work culture. Like many who seek physical labor for their employment, there is a fulfillment that one receives from being actively on their feet, avoiding the tedium of sedentary employment.

This does not mean they are averse to technology. Anyone who owns a smartphone, is accustomed to using a computer to assist in the activities of their everyday lives. Longshoremen are no different.

What American dockworkers need is an implementation of automation that integrates into their culture. Instead of turning the American ports into just another sedentary corporate office job, the U.S. needs to adopt a style of automation without destroying the aspects of the Longshoremen’s work that brings fulfillment to their way of life.

In this manner, industrial smart glasses like DigiLens ARGO, can act as a force multiplier, allowing the same number of dock workers to move substantially more cargo, without compromising the masculine work culture that they share with their military brethren.

A 2015 a study by the New York Shipping Association found that 332 of 582 new dockworkers hired at the Port of New York and New Jersey in the prior 18 months were military veterans (57%).

The solution to American port automation is AR smart glasses (and those smart glasses are ARGO by DigiLens).

|

|

We’ll take a quick look at the outcome of all of UT’s M&A. Then we’ll frame it the context of the military tech challengers emerging out of Silicon Valley, and see how this is all interrelated. I will close the circle. While Ackman won his battle, Hayes moved forward with the additional acquisition of Raytheon. Ackman was opposed to this deal, and divested his holdings in United Technologies only seven months after the breakup he fought for, in May 2019. For his part, Hayes stayed on as CEO of the combined United Technologies and Raytheon, now known as RTX Corporation.

“The stock performance of the top-5 defense primes wildly outperforms the S&P 500… Northrop Grumman, over the last 15 years, has had a total compounded shareholder return of just over 20%. Lockheed and Boeing are just behind them at about 15%. The S&P 500 over that exact same time period has an 11.6% total compounded annual return.” Given all the M&A, it would not be practical to include United Technologies, together with the RockwellCollins and Raytheon acquisitions (without even getting into the Otis, and Carrier spin-offs), given Grimm’s 15 year timescale, however, when judged by their performance in the timeframe since their M&A activity, RTX has not only out performed the S&P 500, but the combined entities (and respective spin-offs) have out performed the rest of the military industrial market, to boot. From 2018 to 2024, the combined value of United Technologies, RockwellCollins, and Raytheon have grown 64%. The resulting RTX has out performed all the other major defense primes in this timeframe as well, with respective increases in value of: General Dynamics at 36%, Lockheed Martin at 53%, Boeing at 46%, and Northrop Grumman close behind at 60%. So the market approved of both Ackman’s breakup, and of Hayes’ acquisitions (too bad for Ackman, he sold so soon)… but the question is: Is the market the right judge? At the end of the day, tax-payers are funding military industrial companies that are profitable for their investors in no small part because they’ve learned how to game the government’s “cost-plus” billing program. This must end. This is not only unethical and scandalous, but they’re taxing (stealing) a tremendous amount of money from the people.

“The challenges with Defense Tech… the two big ones, one is procurement and the process… there the rules around what you can procure to prevent corruption have gotten illogically wild. So, one of them is they purchased via this Cost Plus model which basically says whatever it costs you to build, then we’ll pay you 10% or 20% more than that… The problem with that is [the companies] just spend as much money as [they] can building this thing… and take [their] time… because there’s no penalty for it being three years late, and the technology sucking… the penalty is for not doing that.” In fiscal year 2023, the United States allocated approximately $820.3 billion to military expenditures, constituting about 13.3% of the federal budget for that year. Of this total, about $144.9 billion (17.7%) was designated for procurement, and approximately $130.1 billion (15.9%) was allocated for research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E). These defense sector companies vastly outperform the market because the incentive structure is perverse, and the business model borders on the criminal. Against the inertia of the blob, I hope the new administration makes some kind of progress in restructuring this industry… and audits everyone. It is not just that it is robbing the American people blind, it is clear that with a peer rival on the ascent, and a multipolar world taking shape, if this is not restructured, we will not remain the world’s model army. I’m optimistic about Anduril, and the consortium they’ve formed with Palantir, and I would like to see them reach out to companies like DigiLens. |

|

“The FAA killed the drone industry years ago… The reason why the Chinese are winning in the Drone Wars is because the FAA… made drones illegal in the US… Legally you cannot fly a drone… beyond line of sight if you don’t have a pilot’s license. Which means… [a] US drone… [must] either not fly beyond line of sight… or… validate only [customers] that have pilot licenses. [In] China there’s no such restriction… Chinese drones… [can] just [be bought] in the US and used however you want. Technically… you’re out of compliance with the law, but… they ignore that part [and] just punish the American drone makers. That’s why… 90% of the drones used by the US Military and… police are Chinese-made… Every Chinese drone is… a potential surveillance platform and… weapon.”

—Marc Andreessen, General Partner, Andreessen Horowitz

The growing reliance on Chinese-made components in U.S. military systems, highlighted in reports from Foreign Desk News (July 2024) and Defense One (June 2023), underscores the urgency of securing domestic and allied supply chains. The 2024 report revealed a dramatic increase in Chinese manufacturers supporting U.S. military systems, from approximately 12,000 in 2005 to nearly 45,000 by 2023, including critical semiconductors used in Patriot missiles and B-2 bombers. While the Navy and Army made strides in reducing Chinese suppliers by 40% and 17% respectively in 2023, the Air Force and other agencies increased their dependency, reflecting challenges in mitigating this reliance.

This emphasizes the strategic importance of selecting domestic companies like DigiLens for near-eye display contracts, especially as the number of Chinese waveguide manufacturers grows, posing potential risks to supply chain security.

When the government selects specific companies to fulfill critical defense contracts, it inevitably shapes the market, creating winners but also sidelining potential competitors. While this can accelerate innovation and secure military supply chains, it can also risk stifling competition in the private sector. Whomever the military chooses for this supplier, will inevitably have an upper-hand in the private sector. Philosophically, this has made an endorsement difficult. I’m both a reluctant warrior, favoring diplomacy over force, and an advocate of the free market. Endorsing a supplier for a military contract is a bit outside of my comfort zone.

Though if the military is going to pick a winner, it should be DigiLens.

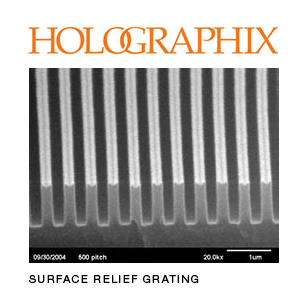

While many other companies have come and gone in the near-eye display space, DigiLens has held a unique position. Like an academy for the industry, many brilliant engineers have come through their lab, and their team is as strong as ever today. DigiLens’ IP portfolio is the envy of the industry. The switchable Bragg grating (SBG) technology that they championed remains the bleeding edge of waveguide technology.

The Crystal 30 lenses used in the ARGO are not DigiLens’ top-of-the-line. That would be the Crystal 50, where a high-speed light engine is alternated through a switchable grating architecture that distributes the light across six regions, expanding to an impressive 50° diagonal FOV. Rather, the Crystal 30 are the sweet spot. They are a 30° FOV display, that can be manufactured at a reasonable price, with high reliability. If the Crystal 50 are DigiLens’ Ferrari F80, then the Crystal 30 are their Ford F150.

But the ARGO platform is far more than a pair of lenses…

Powered by Snapdragon® XR2 Gen 1, 6DoF tracking with camera and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) integration, then center camera is 48MP autofocus, with optical image stabilization (OIS), electronic image stabilization (EIS), and pixel binning for low light scenarios, 12GB LPDDR5 RAM and 128GB UFS storage. It is certified IP65 (dust tight & water resistant), an ANSI Z87.1 safety glasses rating, and the U.S. military’s Extreme Environment Tolerance MIL-STD-810G rating including extreme high & low temperatures, humidity, vibration, shock, and drops.

Google Gemini on DigiLens ARGO smart glasses enable spatial perception and awareness, and provide relevant instructions or tasks to be overlayed into the wearer’s view. By utilizing the glasses’ camera, Gemini can analyze the machine a wearer is working on in real-time.

Gemini’s AI Agents can be proactive: Initiating actions without explicit user prompts. They are goal-oriented, pursuing objectives and will adapting to changing circumstances.

Instead of using predefined voice commands, ARGO can respond to a wide range of conversational languages, enhancing productivity and engagement.

ARGO were designed from the ground up to be an industrial and enterprise user interface for engaging with artificial intelligence, and they are the current state of the art.

Contact Brian Hamilton, Vice President of Sales and Marketing for for a one-on-one demo of ARGO, at ARIA Hospitality Suites, during CES in Las Vegas, NV.

Smart Glasses Battle: Meta vs Snap

Sunday, September 15, 2024 at 9:51PM

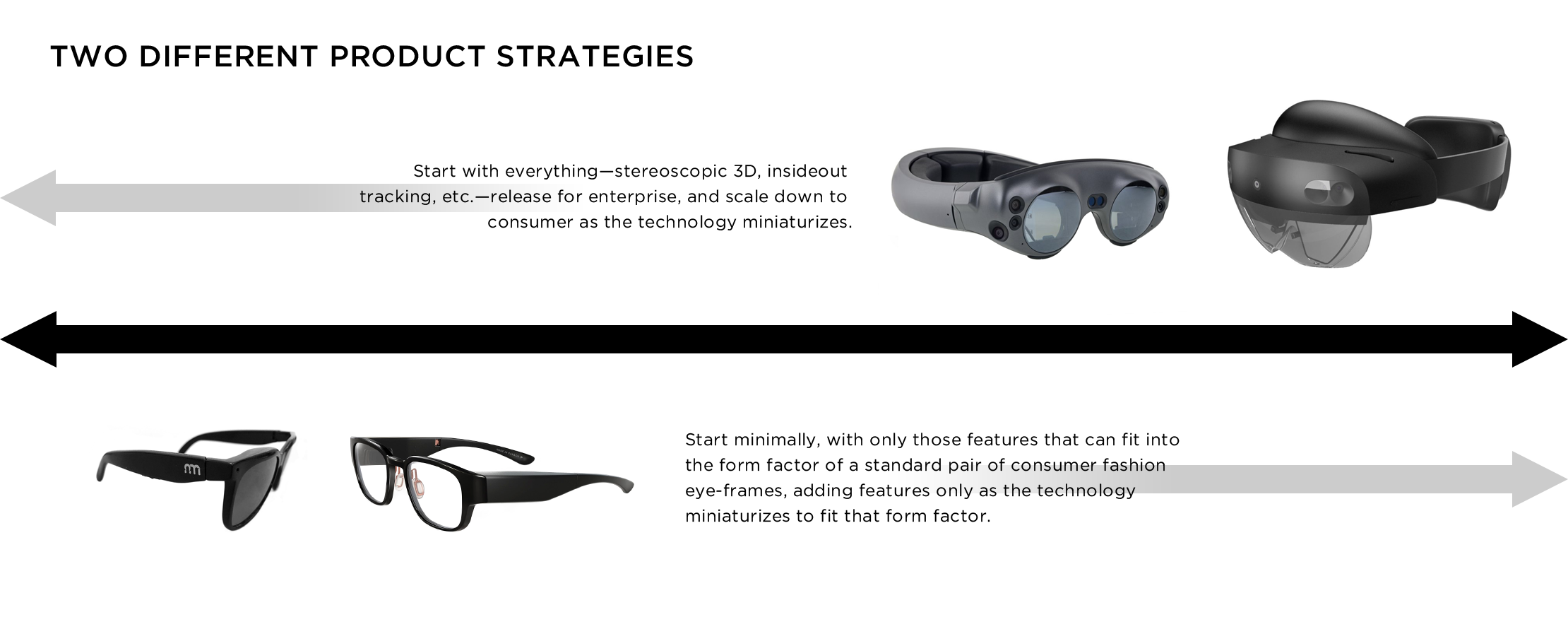

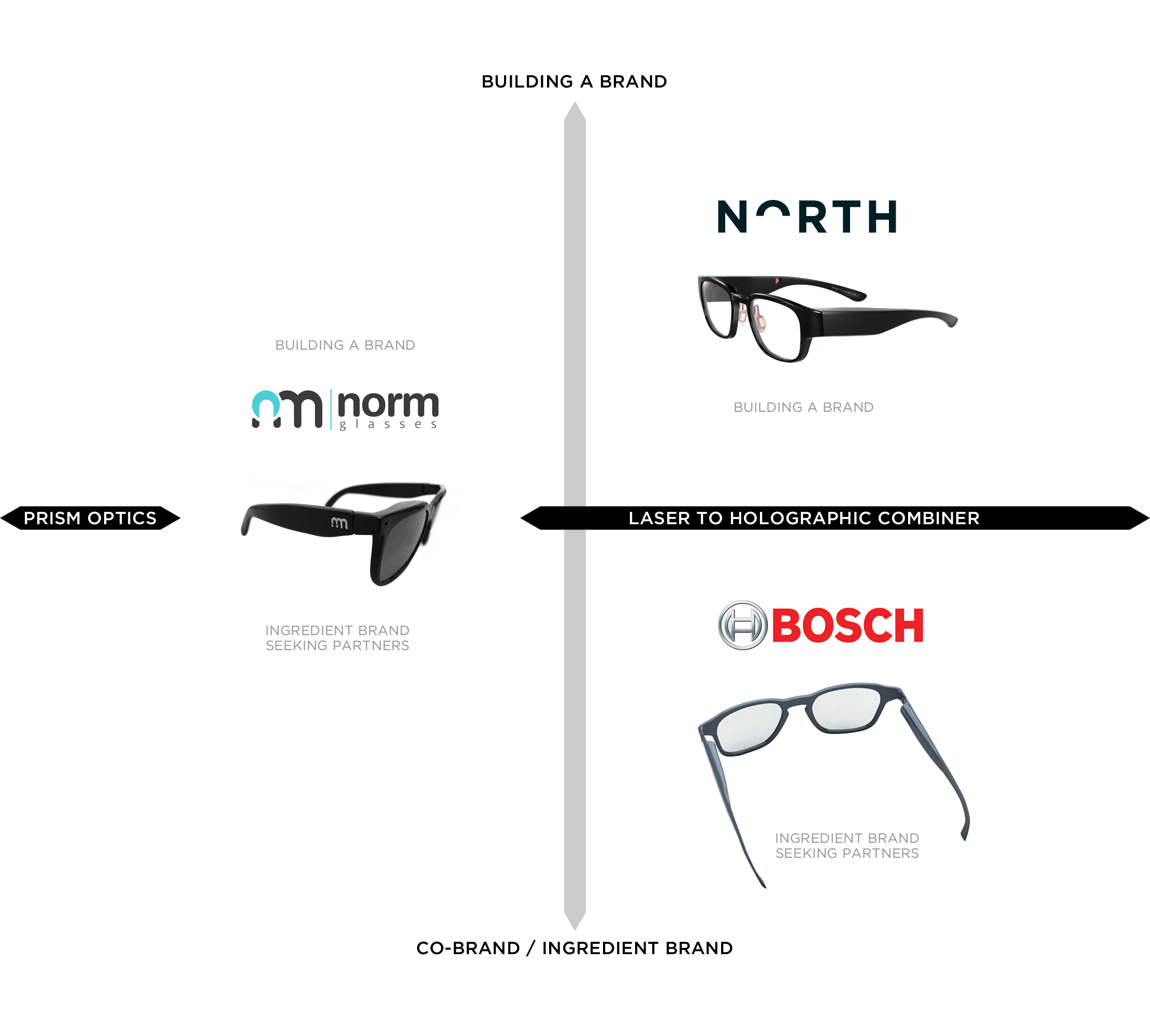

Sunday, September 15, 2024 at 9:51PM In this article we will explore what display technology we might expect to see in the coming days from both Meta and Snap. By display, I mean both light engines and optics. I will then place these displays within the context of what I expect to see from their larger smart glasses system, and the resulting user experience. I will, of course, opine.

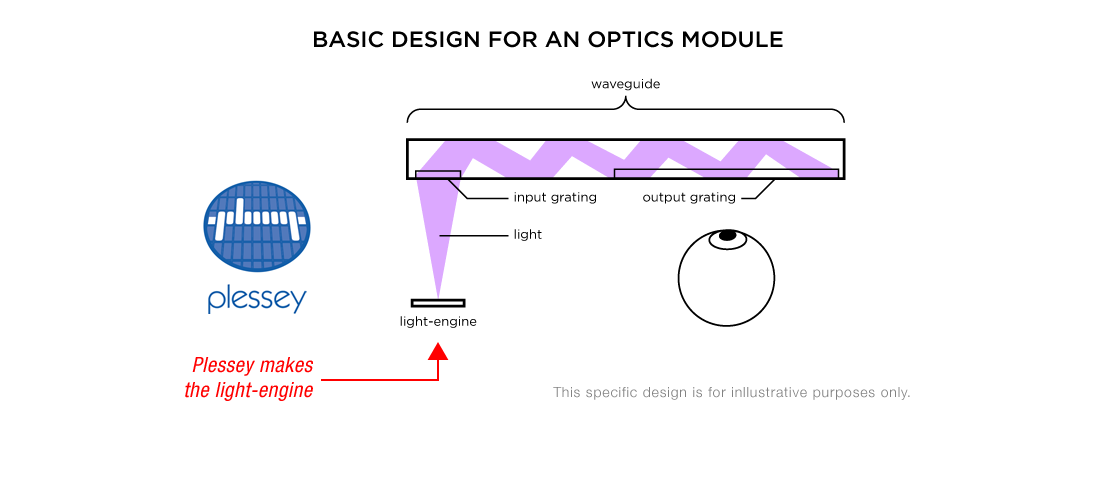

For several years Meta—and everyone else—has been exploring the best way to achieve smart glasses with a wide field of view (FOV). Many have come to the conclusion that a display that divides the FOV up into at least two, and possibly three separate light-engines illuminating a respective number of optical components is the right direction. While the Meta patent art above specifically shows an LBS (Laser Beam Scanner) light-engine, illuminating a holographic combiner, the patent states:

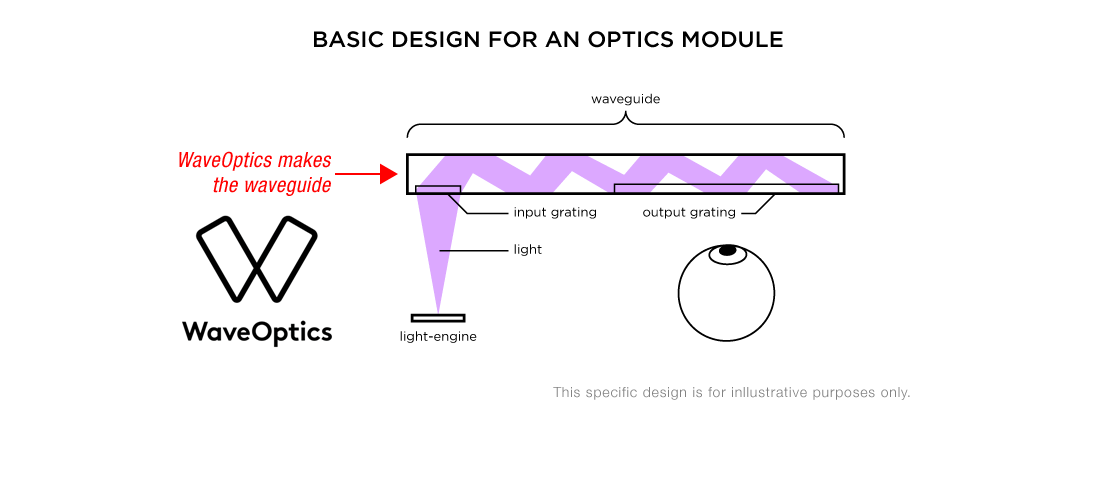

In some implementations, an optical element may comprise a waveguide and/or other components. A waveguide may include one or more of a layered waveguide, a planar 10 partial mirror array waveguide, a diffractive waveguide, a diffractive waveguide including Bragg gratings, a free form surface prism, and/or other waveguides.

…as well as…

[In] some implementations… [the] light source may comprise one or more of… a microLED microdisplay… a liquid crystal display (LCD)… [six other possible light-engines, skipped here by ellipses]… and/or other light sources…

Indeed, the novel proposal is not the particular light-engine used, nor the form of optical components the light-engine is illuminating, but rather a system for compositing multiple light-engines via tiled optical components to expand the field of view (made clear by the title).

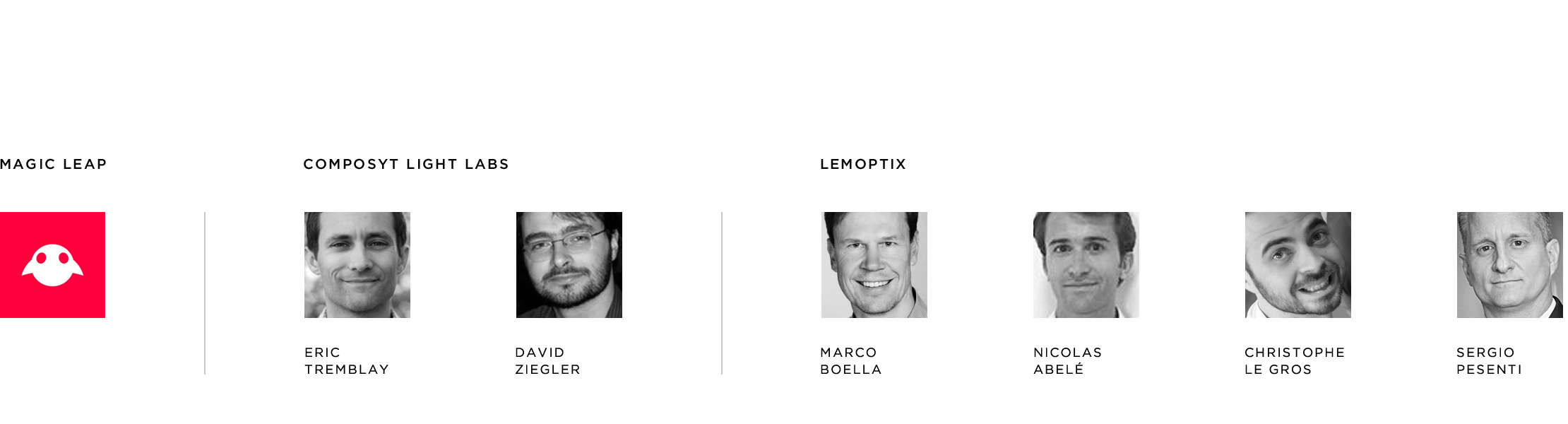

Meta has made acquisitions and built partnerships to achieve these ends.

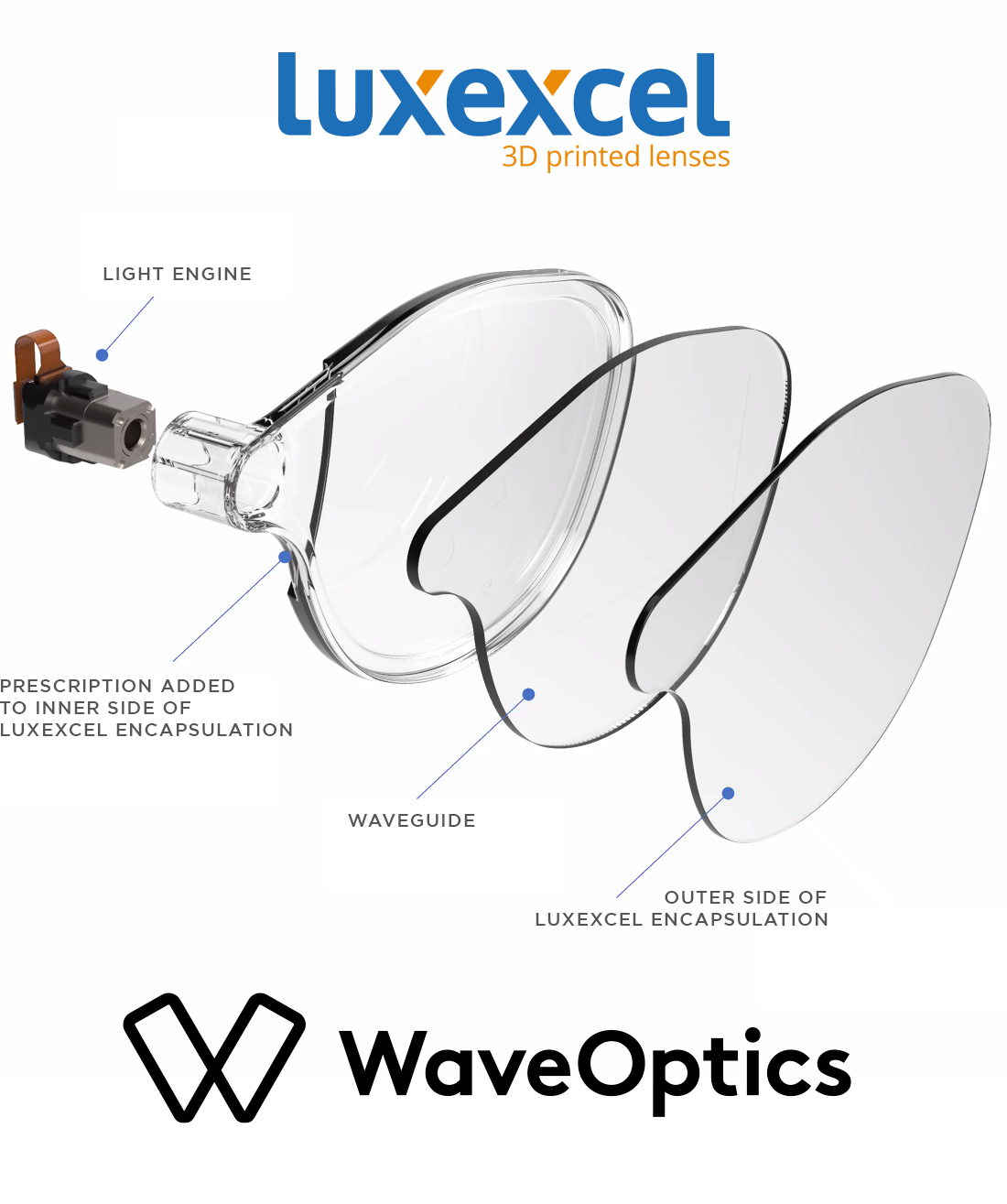

In December 2022 Meta acquired Belgian 3D printed prescription lens manufacturer, Luxexcel, after successfully embedding a waveguide in separate partnerships with both Lumus Optics and WaveOptics (the second of which would themselves be acquired by Snap… which we’ll get to). One year prior, in December 2021 Meta also acquired ImagineOptix, maker of electroactive holographic waveguides. Key inventors listed on their patents now hold Optical Scientist positions at Meta Reality Lab, operating from North Carolina, in a team still led by former ImagineOptix CEO, Erin Clark.

Another interesting development is a key Meta departure, by one Kelsey Wooley. Wooley was a holdover from Facebook’s Oculus acquisition, who had ascended to the position of Engineering Manager over Lithography for Augmented Reality Waveguides, before departing to join Eulitha AG, as Director of North American Operations. Eulitha is a manufacturer of optical mass manufacturing equipment. Earlier this year they debuted their newest line of photolithographic contactless optical manufacturing line with a unique breakthrough: the ability to mass-manufacture curved waveguides (a eureka moment).

Another interesting development is a key Meta departure, by one Kelsey Wooley. Wooley was a holdover from Facebook’s Oculus acquisition, who had ascended to the position of Engineering Manager over Lithography for Augmented Reality Waveguides, before departing to join Eulitha AG, as Director of North American Operations. Eulitha is a manufacturer of optical mass manufacturing equipment. Earlier this year they debuted their newest line of photolithographic contactless optical manufacturing line with a unique breakthrough: the ability to mass-manufacture curved waveguides (a eureka moment).

Last October, Switzerland based Eulitha opened a new office in Redmond, Washington, that Google Maps estimates is a three minute drive to Meta Reality Lab’s Origin office (and no further than four minutes from any published Reality Lab Redmond office address).

So to recap: The former ImagineOptix team designs holographic waveguides. Eulitha makes equipment for mass manufacturing such waveguides (on a curve, no less). Their North American operations are now run by Meta Reality Labs’ former Engineering Manager over Lithography for Augmented Reality Waveguides, and she now operates a Eulitha office close enough to hit Meta Reality Labs’ offices with a rock, thrown from their respective parking lot (ok, you’d have to have a really good arm, or a small trebuchet… but still).

“[When] printing on curved glass… the extremely large depth of focus is one of the benefits of these DTL tools. That it’s able to print over non-planar substrates, topography, and curved substrates very well,” said Kelsey Wooley, in a recent interview. Eulitha’s photolithography systems are able to print gratings onto a curved lens with over 3mm height difference between the edge and the center, of a 4’ lens.

We can see Meta’s display taking shape. Rumor suggests these displays will be 90°, but the technology could theoretically expand even father… provided you had the light-engines to illuminate them.

The death of MicroLED Microdisplays has been greatly exaggerated.

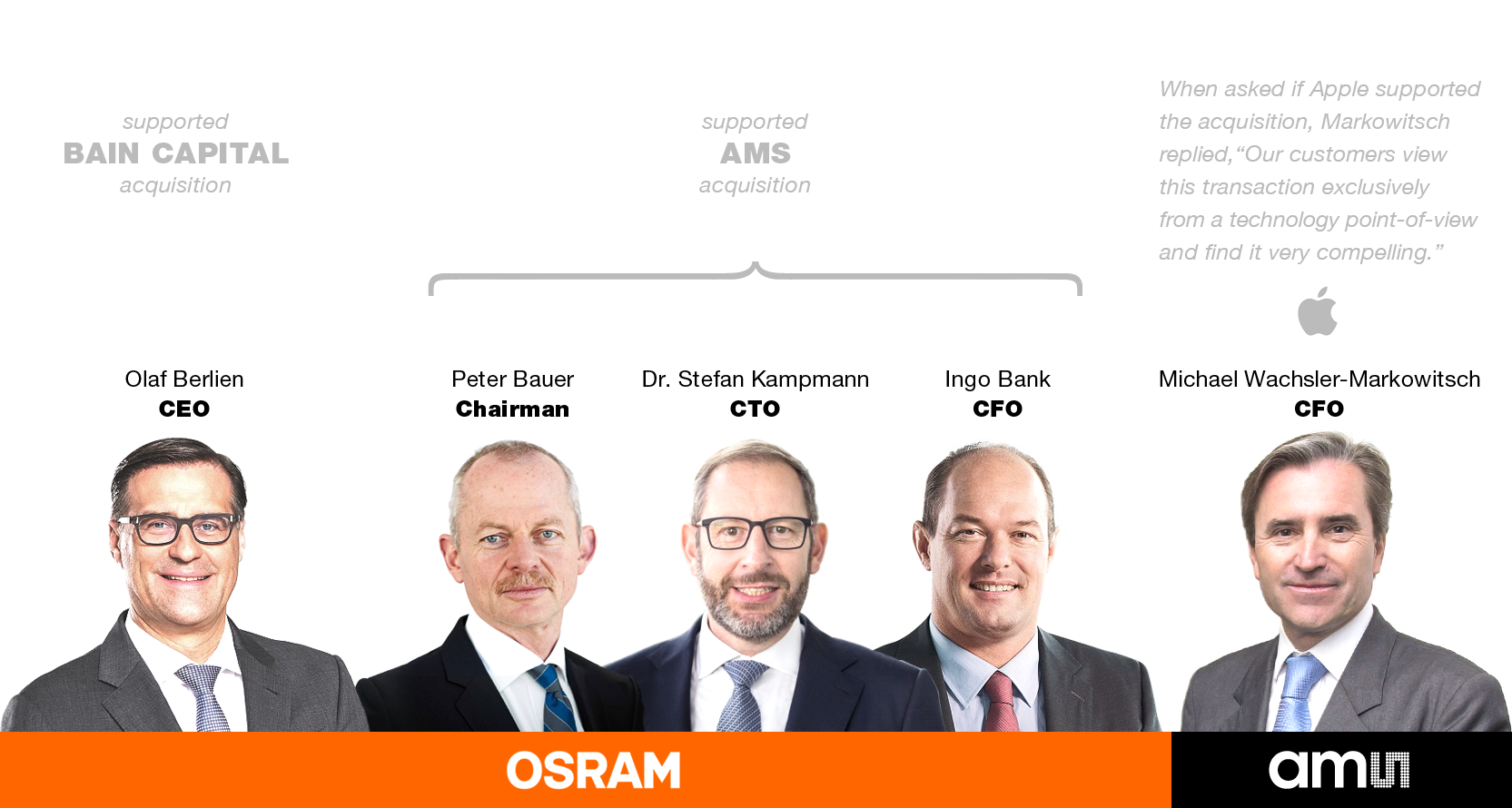

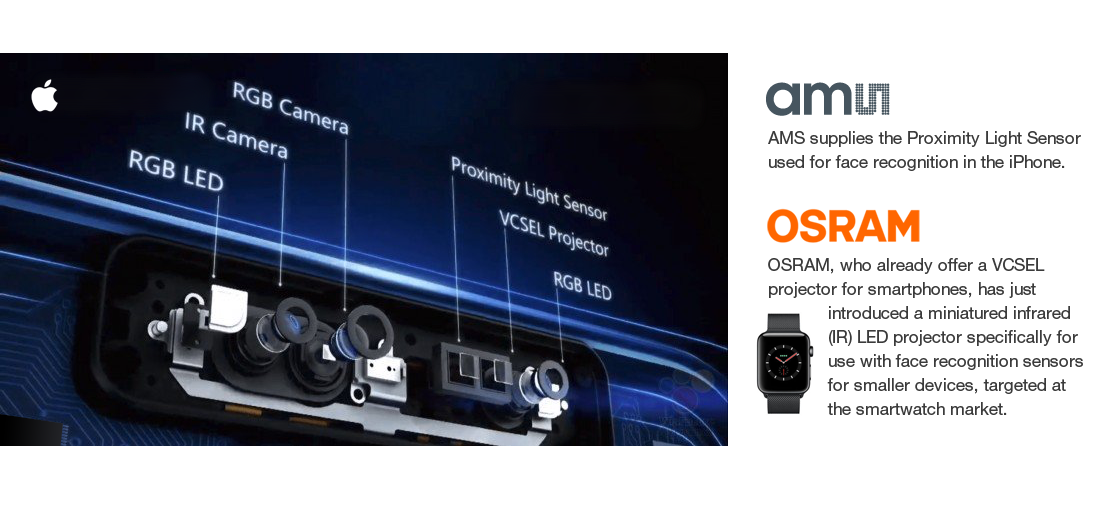

In March of this year, it was revealed that Apple was canceling their MicroLED based Apple Watch Ultra, as well as canceling their MicroLED microdisplay manufacturing contract with amsOSRAM in the process. This was subsequently interpreted by the tech press as the death of MicroLED itself, and propagated as accepted wisdom: MicroLED was dead.

Long live MicroLED.

At that time I was in the very thick of producing an industry report on MicroLED microdisplays, so I was speaking to many in the near-eye display industry regularly, specifically about MicroLED microdisplays for use as light engines for smart glasses. The perception gap between the press coverage on “the death of MicroLEDs” versus the point of view of those in the industry was tremendous, particularly from waveguide manufacturers: The naysayers are either using hyperbole for engagement harvesting and site traffic, or they were simply foolish people (or both).

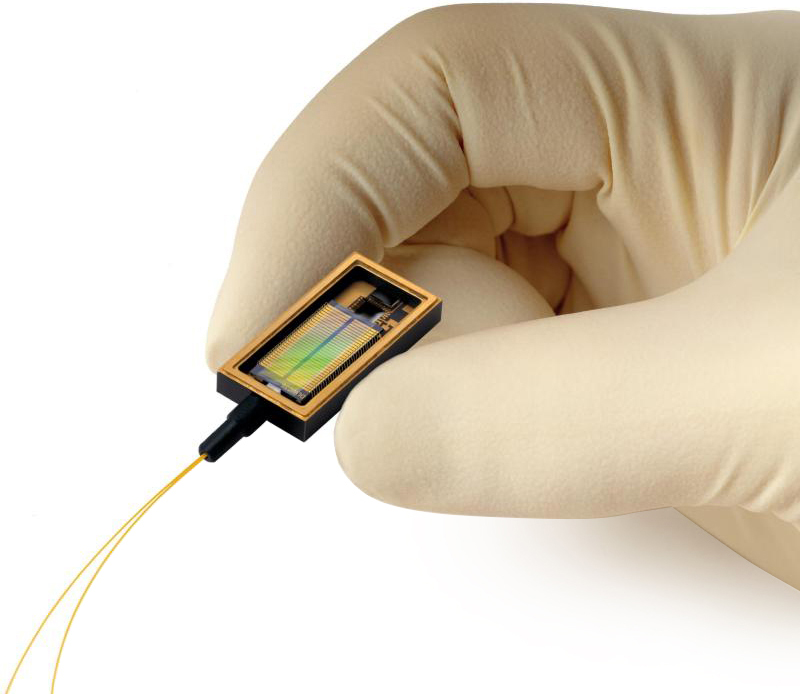

A deep dive on the Apple / amsOSRAM contract cancellation is beyond the scope of this article, but here are a few cogent points: Yes, as with all emerging technologies, MicroLED microdisplays have real challenges. Many have struggled with the miniaturization of the interconnects—think of them as the “wires” that power each individual diode—which must scale at parity with the diodes themselves. This has bedeviled many microdisplay developers. Hence, it has been typical for companies to partnered with others in the semiconductor space for their backplane expertise.

The real struggle is to produce MicroLEDs at volume, and to do so at high yield such that imperfections resulting in rejected units don’t eat away margins, so that cost per unit can be made practical for use in a market viable consumer product. In other words, quite similar to the struggles typical of every emerging new core technology.

Hardware is hard.

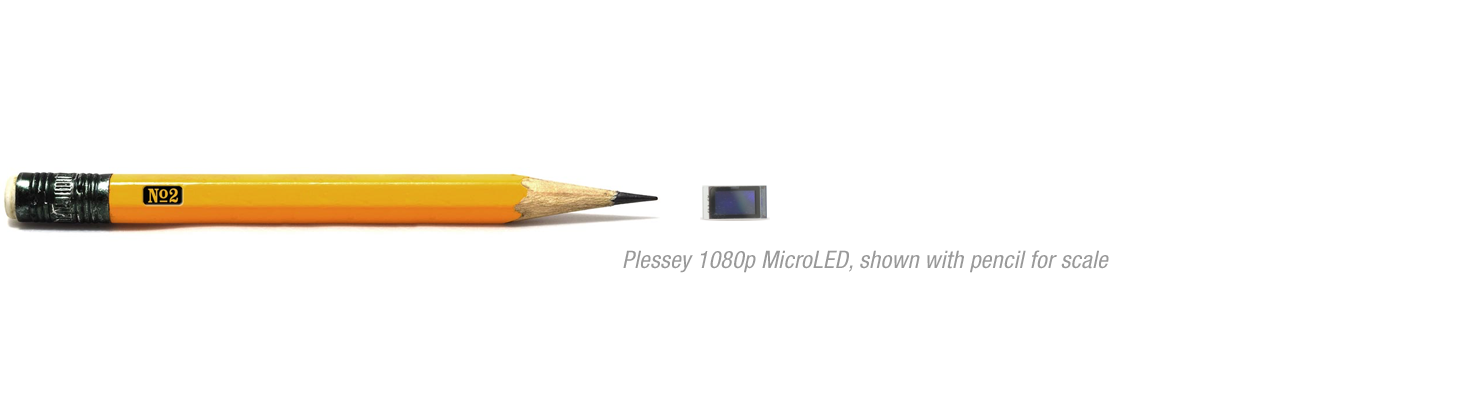

But when it comes to displays, the promise of MicroLED is without peer. The belief that, for smart glasses to succeed in the consumer market, they must have a wide field of view, but sufficiently miniaturized in size so as to fit into the form factor of a consumer-viable eye-wear design, yet also have low power consumption to keep the battery small, while retaining good uptime between charges. With these market demands for success, MicroLED is without peer.

At this moment MicroLED microdisplays are simply too expensive to produce at a market viable price point, and even the expensive mass manufacturing methods available don’t produce acceptable yield, for full color microdisplays… yet.

It is going to take high volume production to get to economies of scale for a consumer price point pair of MicroLED run smart glasses. This is where the Apple Watch came in.

If Apple wants to use MicroLED microdisplays for future smart glasses, they have an ace up their sleeve, or at least an Apple Watch under their cuff. If Apple produced a MicroLED microdisplay based Apple Watch as they had planned to do with the Apple Watch Ultra, they could use their existing high-volume wrist-worn wearable to bring economies of scale to MicroLED microdisplay production, lowering their production cost for other uses… such as smart glasses.

So while many in the tech sphere positioned the order cancellation purely as a technological failing, I believe there was more to it. Sure, for reasons stated above, there were presumably genuine concerns over whether amsOSRAM could deliver. But even if amsOSRAM had nailed it, there was an additional business concern: Apple likes exclusivity.

Tim Cook comes out of supply chain management. When there is a market differentiator, Apple likes to lock down supply. For their part, amsOSRAM was using the substantial Apple contract to fund what was billed as the world’s largest MicroLED factory. This would create much more capacity than Apple needed or likely would commit to paying for the exclusivity, for that volume of output. That would mean that Apple would be underwriting the cost for the whole industry, and likely footing the bill to bring down the cost for competitors who could then beat them to market with MicroLED microdisplay smart glasses, from amsOSRAM’s production line… all on Apple’s dime.

I emphasize, I have no Apple insider knowledge on this, it is speculation on my part, but speculation that fits Apple’s modus operandi, and it appeared to me likely that beyond technical concerns, there was a disconnect at amsOSRAM in understanding Apple’s business needs.

More pertinent to our story…

The death of Plessey has also been greatly exaggerated.

In July of last year, Wayne Ma wrote a report in The Information on various leaks regarding Meta’s smart glasses progress. While Ma’s report covered many aspects of Meta’s development, I’m principally concerned here with his coverage of their light engine, where it was suggesting that Meta was abandoning Plessey’s MicroLED microdisplay in favor of an LCoS microdisplay (though the article does walk it back a bit at the end). The report reads more accurate than many secondhand interpretations. The tech blog-o-sphere ran with the death of Plessey, which is now conventional wisdom in online chatter and industry shop-talk, whenever I mention the company.

Long live Plessey.

So what is my Plessey scoop? Everything I am going to share here is publicly available. When a company is in crash-and-burn phase, there are typically some, well, obvious tell-tale signs: Have they had massive layoffs? According to Linkedin headcount, Plessey has 204 employees, and have lost 5% in the past year (given recent tech layoffs, a 5% headcount reduction doesn’t look bad at all). Are key personnel departing? I can only find two Sr. management departures in this window: Jun-Youn Kim, Plessey’s former VP of R&D, left a couple months before The Information’s story broke (departing for a similar position within Samsung’s MicroLED group); and Ariel Meyuhas, a self described “operational turnaround” expert, and Plessey’s former COO departed just recently, but wasn’t even hired until after The Information’s story ran. I guess Meyuhas’ task was complete. Has the CEO or CTO been pushed out? Keith Strickland has been, and remains both CEO & CTO of Plessey.

Plessey has also continued producing bleeding-edge MicroLED microdisplay IP. If the reader will indulge me for a moment—both from an engineering and aesthetic point-of-view—Plessey produces some of the most pleasing patents in the industry.

Just look at that pixel!

Wayne Ma’s story concludes:

People familiar with Meta’s MicroLED efforts say it hasn’t given up on the technology and will continue working on it with Plessey, though it isn’t clear when it will be ready for prime time.

So the story out of The Information was not nearly as apocalyptic of Plessey as the rumor mill that resulted (perhaps because The Information is behind a paywall, most only knew the rumors).

Earlier in his article, Ma noted:

Meta’s decision to abandon Plessey’s microLED technology means it is reliant on an older technology for its AR glasses. MicroLEDs contain pixels that are microscopic in size and are difficult to produce… By contrast, LCoS was first introduced… in the 1990s. The technology isn’t known for its brightness, which is a major requirement of AR products…

Let’s talk more about light engines…

MicroLED adaptive-illuminated LCoS light engines, to be specific.

MicroLED remains the industry’s long-term solution, but the patent record shows many have been simultaneously exploring a stop-gap hybrid MicroLED / LCoS microdisplay.

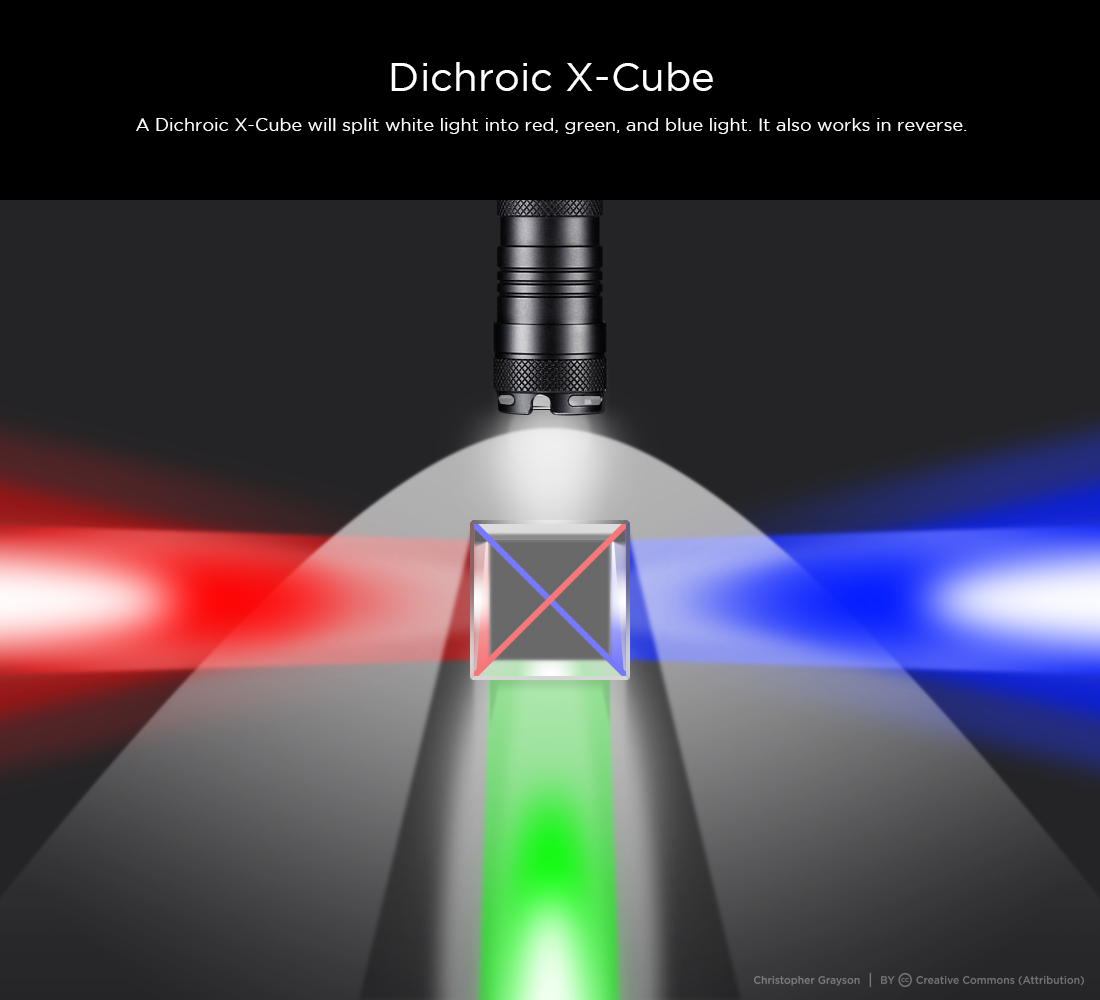

A quick explainer: Liquid crystals are non-emitting, that is to say, they produce no light of their own. When electricity is applied to liquid crystals their optical properties can be altered from a highly transparent state to a substantially opaque one, thereby modulating the light, when paired with a light source. A liquid crystal display typically has a fully-lit backlight. To produce colors, they also require non-emissive color filters in front.

Note again that many of the most difficult struggles with MicroLED microdisplays concern the mass manufacturing of full-color displays.

Creating a single-color white (blue-ish “cool white”) MicroLED circumvents these challenges, and can be used as a backlight for an LCoS microdisplay, but unique in that it only illuminates individual pixels or sub-pixels, as needed.

Given that smart glasses are producing imagery over the real world, anything that is “transparent” is an unlit pixel in the light engine. An LCoS display using a MicroLED backlight that only illuminates on a pixel-by-pixel basis will give both better image quality, as well as much lower power consumption… and it can produce RGB at a much lower cost than any current pure MicroLED based microdisplay (substantially so).

While many have been pursuing R&D in this direction, as of this past January, Avegant and Lumileds were first to take their partnership to market.

So who has IP, R&D, and/or known displays using MicroLED illuminated LCoS microdisplays?

Two of those companies are Plessey and Compound Photonics, the former under exclusive supplier contract to Meta, and the later acquired by Snap.

Everyone who partnered with Plessey was quickly acquired—Compound Photonics (CP) was snapped-up by Snap, Jasper was gobbled up by Google (sorry, I had to)—but interestingly CP had a long history in LCoS microdisplays. Naturally they were one of the earliest to develop MicroLED illuminated LCoS microdisplay IP.

It’s all very synergistic, it’s not like one cutting off from the other… We’re a microdisplay company—we’re not a MicroLED company, we’re not an LCoS company… we’re going to make the best performing, smallest form factor displays we possibly can…

—Mike Lee, then CEO of Compound Photonics, from SPIE Fireside-Chat 2020

So not only should we expect to see Plessey working with Meta on a MicroLED illuminated LCoS microdisplay, but we should expect the same from Snap’s smart glasses.

In a moment we’re going to see what we should expect to be different, from a use case / user experience between Meta and Snaps, but first we’re going to bring this full circle: Snap has also recently been awarded a patent for a multi-light-engine waveguide (two, in this case), and we’re going to pair it with their 3D sensing camera IP, as it is central to Snap’s use case.

Meta & Snap Use Cases

With these technologies working in tandem, Snap’s glasses should have both the wide FOV display, and the three dimensional understanding of their content to display the kind of filters Snap is famous for on their Snapchat platform, and their IP reflects that intent.

From the patent, in reference to the art above…

…if the user wishes to apply augmented reality lenses to the captured image, the augmented reality lenses would be selected based on the objects in the display and applied to the objects in the portion of the real-world image that is shown in the display. For example… a face may be recognized that is captured in the display and an augmented reality lens applied (in this case, the features of a dog). In this example, the lens including the dog features would [also] be applied to the face of the second person as shown…

Those familiar, may recall Snap’s 2021 demo was promising, but with a narrow FOV. I expect Snap’s content to be on-brand, polished visuals, but now with an expanded wide field-of-view and to show more virtual content directly interacting with people, like their app filters.

I expect the content for Meta’s glasses to build on their previous audio demo, bring AI into the display. I’m going to close with a preview of Ramblr.AI’s recently released demo real. Ramblr is a newly launched AI / AR interface for the physical world. It is the latest from Thomas Alt, he the former founder of AR platform, Metaio, who exited to Apple, back in 2015. While I anticipate something more polished, interface-wise, from Meta’s demo, I anticipate similar visual AI use cases (I also expect Ramblr to evolve quickly).

Thomas Alt—former founder of Metaio (Apple acquisition 2015)—has just unveiled Ramblr AI, an artificial intelligence driven OS and development platform for smart glasses. pic.twitter.com/UT3tcLijqv

— Christopher Grayson (@chrisgrayson) September 6, 2024

Christopher Grayson is a marketer, and an independent market analyst on near-eye optics displays, the consumer eye-frames industry, and the smart glasses market. As a writer, he specializes in deciphering technical subjects for an educated but non-engineering audience. Grayson has worked as a marketing director and a PR consultant to various companies in the smart glasses space. He pivoted client-side after a career in the New York advertising industry, working for agencies such as Ogilvy, and Grey Advertising, producing award winning campaigns for Intel, Nikon, and others.

Grayson majored in architecture at Pratt Institute in New York, with prior studies in the contemporary cultural anthropology of humans and technology at Memphis State University.

Contact for consulting projects: chris@chrisgrayson.com

https://t.co/ZW8JqZQ89p pic.twitter.com/P5ERLfvjiH

— Christopher Grayson (@chrisgrayson) September 17, 2024

AWE 2024 XR Gallery

Wednesday, June 26, 2024 at 12:00PM

Wednesday, June 26, 2024 at 12:00PM AWE 2024 was held at Long Beach Convention Center, June 18-20.

A selection of photographs by Chris Grayson.

Share.

XR GALLERY — Photos & Device List for the XR Gallery, from Augmented World Expo #AWE2024, Long Beach, California. Link in the quote-tweet below… https://t.co/V4oHq2xwYG pic.twitter.com/w7qaWIrK7L

— Christopher Grayson (@chrisgrayson) June 26, 2024

| Brand | Product | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Sawyer | View-Master Model C | 1946-1955 |

| Unbranded (likely Underwood) | Victorian Stereoscopes | 1800s |

| Goggle Tech | C1-Glass | 2016 |

| Forte | VFX 1 | 1992 |

| Nintendo | Virtual Boy | 1995 |

| Tiger Electronics | R-Zone | 1997 |

| Radica | NASCAR i-Racer | 1999 |

| Hasbro | Hero Vision AR (Iron Man) | 2018 |

| Toy Quest | VR World 1 | 1994 |

| Toy Quest | VR World 3 | 1997 |

| Virtuality | Viset 1 | 1992 |

| Virtuality | Viset 2 | 1995 |

| Takara | Scuba VR | 1998 |

| Virtual i-O | i-Glasses | 1996 |

| Virtual i-O | i-Glasses VGA prototype | 1996 |

| Vuzix | Wrap 920AR | 2010 |

| Microvision | Nomad ND 1000 | 2002 |

| Microvision | Nomad Expert Technician System | 2006 |

| Sony | VAIO VGN-U750P | 2004 |

| Sony | VGN-UX380N | 2007 |

| Stereographics | CrystalEyes CE-1 | 1989 |

| Reflection Technology | Private Eye | 1989 |

| Sony | LDI-D100BE | 1999 |

| Minolta | Forgettable Near-Eye Display (prototype) | 2000 |

| Microsoft | HoloLens 1 | 2016 |

| Microsoft | HoloLens 1.5 | 2017 |

| Microsoft | HoloLens 2 | 2019 |

| Osterhout Design Group (ODG) | R-6 | 2014 |

| Osterhout Design Group (ODG) | R-7 | 2015 |

| MagicLeap | MagicLeap 1 | 2018 |

| MagicLeap | MagicLeap 2 | 2021 |

| MicroOptical | EG-2 | 1997 |

| MicroOptical | EG-7 | 1997 |

| MicroOptical | Concept | 1998 |

| MicroOptical | Lipstick | 1999 |

| MicroOptical | Task-9 | 2000 |

| MicroOptical | CV-1 | 2001 |

| MicroOptical | CV-2 | 2002 |

| Oculus | DK1 | 2013 |

| Oculus | DKHD | 2013 |

| Oculus | DK2 | 2014 |

| Oculus | Prototype | — |

| Oculus | Crescent Bay (prototype) | 2015 |

| Oculus | Rift S | 2019 |

| Oculus | Quest 1 | 2019 |

| Oculus | Quest 2 | 2020 |

| Oculus | Quest 3 | 2023 |

| Oculus | Palmer Luckey’s Personal Prototype | — |

| Icuiti | M920 | 2005 |

| Icuiti | V920 | 2005 |

| Vuzix | Wrap 1200 | 2011 |

| Vuzix | Video Glasses | — |

| Vuzix | M300 | 2017 |

| Vuzix | M400 | 2019 |

| Vuzix | AV230 | 2008 |

| Vuzix | iWear (limited edition) | 2007 |

| Vuzix | iWear (video headphones) | 2015 |

| Vuzix | Blade 1 | 2018 |

| Vuzix | AV310 | 2008 |

| Vuzix | M100 (Parks & Recreation, Gryzzl edition) | 2013 |

| Vuzix | Smart Swim | 2020 |

| MyVu | Shades | 2007 |

| MyVu | Crystal | 2008 |

| MyVu | Viscom | 2010 |

| META | Meta 1 | 2014 |

| META | Meta 2 | 2016 |

| Telepathy | Walker | 2016 |

| DigiLens | DL30 | 2019 |

| XREAL (formerly nreal) | nreal light | 2021 |

| XREAL | XREAL air2 | 2022 |

| XREAL | XREAL air2 Pro | 2023 |

| XREAL | XREAL air2 Ultra | 2024 |

| Wearality | Wearality VR | 2015 |

| Epson | Moverio BT-1 | 2012 |

| Epson | Moverio BT-2 | 2014 |

| Virtual Vision | VirtualVision | 1993 |

| Mira | Prism | 2018 |

| Lenovo | Think Reality | 2021 |

| Microoled | Engo 2.0 | 2023 |

| Everysight | Raptor | 2017 |

| Dreamworld | Dreamworld | 2018 |

| Lumus | DK50 | 2017 |

| Digioptix | Smart Glasses | 2016 |

| Avegant | Glyph | 2014 |

| Lenovo | Star Wars: Jedi Challenges | 2017 |

| generic | High FOV AR | 2017 |

| Daydream V1 | 2017 | |

| Daydream V2 | 2018 | |

| Mictic | Mictic One | 2022 |

| Thalmic Labs | MYO | 2015 |

| Litho | Litho (wearable controller) | 2019 |

| Fakespace | FOV2GO Model A | 2012 |

| Fakespace | FOV2GO Model D | 2012 |

| Fakespace | Smartphone HMD | 2011 |

| Mixed Reality Research Lab | VR2GO iPhone | 2013 |

| Mixed Reality Research Lab | VR2GO Galaxy | 2013 |

| Fakespace | USC MxR “Franken-Viewers” | 2011 |

| — | 7x Lens | 2012 |

| NASA Viewlab | NASA Head Mounted Display | 1988 |

| NASA Viewlab | HMD Electronics System | 1988 |

| NASA Viewlab | NASA Data Glove | 1987 |

| NASA Viewlab | Window Box | 1986 |

| PopOptix | LEEP Viewer & Lens Assembly | 1979 |

| NASA Viewlab | Convolvotron | 1988 |

| Fakespace | Wide 5 HMD | 2004-2007 |

| Fakespace/Phasespace | Augmented Reality Optics | 2009-2012 |

| — | Head-Mounted Projector | 2009-2012 |

| Disney/NVIS | Disney Quest Aladdin Headset | 1996 |

For consideration for your further reading pleasure…

MicroLED Microdisplays Report + Supplemental

Saturday, June 15, 2024 at 6:30PM

Saturday, June 15, 2024 at 6:30PM

Featured Companies can reach out to me for a 10% off Coupon Code.

If you see your company listed below.

This 2024 Consumer Smart Glasses Report is focused on the latest developments in near-eye display technology. This is a business report written to be readable by an educated but non-engineering audience… containing plenty that an engineer would find of value, too.

The focus is on MicroLED microdisplays, put into the context of other competing light engine technologies, and includes an in-depth summary of the latest in waveguides, embedded within corrective optics.

There are many reports that cover MicroLEDs, there are no others specific to MicroLED Microdisplays.

What MicroLED microdisplay companies are profiled?

39 COMPANIES PROFILED

The 39 MicroLED microdisplay companies listed below are profiled. A few of these companies have been acquired. The details of their exit are included. One has since abandoned work in microdisplays (though continues work in large format MicroLED displays), after an initial foray in microdisplays development.

There are many other display companies experimenting in MicroLEDs that are explicitly NOT pursuing microdisplays. Those companies are not included. ONLY MicroLED companies that have done R&D specifically in microdisplays are profiled in this report.

What do these profiles include?

PLEASE READ

Each contending company in the MicroLED microdisplay market has a profile page that begins with a table of known specifications, documenting their R&D progress. With few exceptions, most do not yet have a microdisplay in the market. Sourcing a combination of press releases, white papers, trade show coverage, and executive interviews, a table of all known prototype specifications has been built. While a few have not released any specs at all, most have at least one prototype, while others have more than a half-dozen. In a few cases companies agreed to share exclusive specifications when contacted. The tables are not cookie-cutter. Different companies choose to highlight different specs.

Each profile is unique.

The body of NOTES covers the company background, notable executives, technological implementation (especially anything that might differentiate), academic research, patent filings, partnerships, milestones, and any other noteworthy business matters.

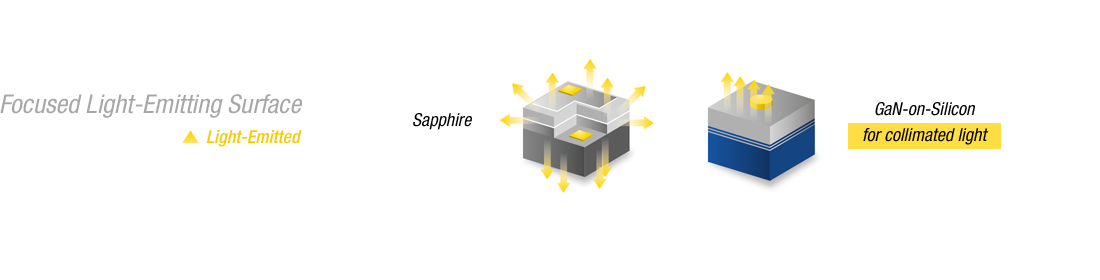

Given their extreme miniaturization, one characteristic unique to MicroLEDs is that commodity collimation optics—that is to say, the optics that steer light rays to move largely uniformly in the same direction, perpendicular to the plane of the display—have become the primary source of bulk in the light engine module. As a consequence, I afforded more attention to miniaturization of the collimation optics than might otherwise be typical in such a report, as I consider it existential to the success of MicroLEDs. What good is the smallest display ever mass produced, if it requires collimation optics, five or even ten times the dimensions of the display itself?

Most profiles contain at least one left sidebar. Depending on the company this may cover a unique technological approach or achievement, profile a specific partnership or relationship, or include an executive or founder profile.

Many profiles include an image of a prototype, or an illustration from a patent.

The first profile in the report is that of French startup Aledia—they have only just recently released specifications for their first publicly revealed prototype.

SAMPLE PROFILE PAGE

What else is included in the report?

93 PAGES

The report opens with a 15 page state-of-the-industry, explaining why MicroLED microdisplays are a crucial break-through technology, placing them in the context of other developments within the smart glasses industry, and explains the author’s unique point of view: how MicroLEDs fit into the larger goal of getting to a low-profile consumer-viable product (i.e.: getting to consumer smart glasses that will both viable pass for regular prescription glasses, or sunglasses, that are fashionable, with a feature-set that will exceed consumer’s high expectation).

The report covers competing engineering designs for achieving full-color RGB MicroLED microdisplays at high-yield scalability. Extensive focus is also given to micro-collimation optics, necessary to substantially reduce the bulk of the light engine.

STATE OF THE INDUSTRY TEASER PAGES

There are seven charts and graphs showing how MicroLED microdisplay specifications have evolved overtime, and comparing their specifications to other competing display technologies, such as LBS, DLP, OLED, & LCoS.

BY THE NUMBERS TEASER

There is a 10 page supplemental section, showcasing ten waveguide manufacturers who are now known to have achieved a waveguide within a prescription lens.

WAVEGUIDE SUPPLEMENTAL TEASER

There is a chapter, “Coming Together,” on how MicroLED microdisplays, prescription waveguides, and other related breakthroughs will get us to a consumer viable smart glasses product.

COMING TOGETHER TEASER

Featured Companies can reach out to me for a 10% off Coupon Code.

If you see your company listed above.

Endorsed by Tipatat Chennavasin, General Partner of The Venture Reality Fund.

This is really well researched. If you want to know what the state of the art of optical #ar display tech is, I highly suggest buying this report #spatialcomputing https://t.co/3dJGewHfdp

— tipatat (@tipatat) June 19, 2024

Italian Glasses? Smart.

Monday, June 14, 2021 at 1:58PM

Monday, June 14, 2021 at 1:58PM

Parallel to the tech industry’s own decade-long R&D investment, and strategic pursuit of consumer smart glasses, a second battle has been playing out in near choreographed tandem, yet virtually invisible to most inside the Silicon Valley bubble.

If the tech industry’s watershed date of April 15, 2013 saw the introduction of Google Glass crystallizing the tech industry around the pursuit of the next logical human-machine paradigm—that smart glasses are inevitable—across the pond a completely unrelated set of events were put in motion that have reconfigured the premium eye-frames market.

While these two sets of unrelated events have unfolded on the same timeline, most in the tech industry remains blissfully unaware—unaware of the companies concerned, the players involved, or the dynamics shaping the industry.

This article will educate on where the eye-frames industry has been, where it’s going, and in some specific cases of interest where it has already intersected with the tech industry, in order to enlighten us to where opportunities exist.

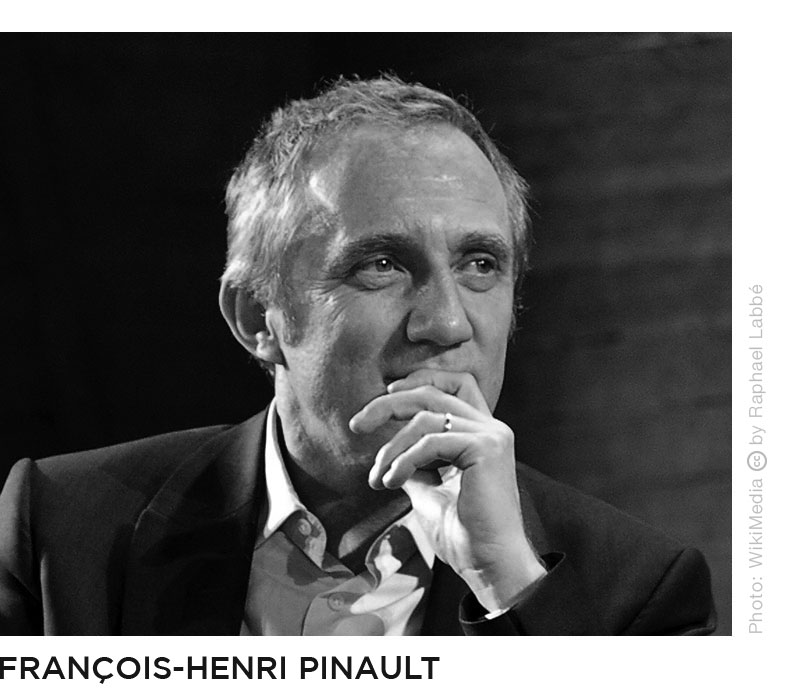

In March of 2013 the French conglomerate of Pinault-Printemps-Redoute (PPR) announced their rebranding as Kering—the culmination of an earlier transfer of power from father to son, that in turn led to a corporate restructuring.

François Pinault (the elder) had diversified the lumber yard he founded in the 1960s into other industries and interests across the French economy, and eventually ran the holding company’s investment portfolio a bit like a private equity firm, with substantial investments across many French industries. Most notably, through this diversified national investment strategy, by the late 90s PPR had acquired shareholder dominance in the French fashion house of Gucci.

The chairmanship and reins of the family empire were fully transferred to François-Henri Pinault (the younger) in 2005 who—through a process of asset liquidation, and subsequent acquisitions—moved the company his father built from a diversified national conglomerate, to a vertically integrated global fashion and luxury goods brand stable—flipping from >90% French domestic revenue, to >90% international revenue.

The chairmanship and reins of the family empire were fully transferred to François-Henri Pinault (the younger) in 2005 who—through a process of asset liquidation, and subsequent acquisitions—moved the company his father built from a diversified national conglomerate, to a vertically integrated global fashion and luxury goods brand stable—flipping from >90% French domestic revenue, to >90% international revenue.

As part of their rebranding and reorganization, Kering did extensive research on the international fashion and luxury goods industry, leaving nothing to assumption or conventional wisdom.

One question Kering wished to answer: What is the first brand touch-point of a Gucci buyers who becomes a lifelong customer?

The conclusion? Sunglasses. There was just one problem…

…Gucci eye-frames were not even made by Gucci, or by Kering at all, but through a brand licensing deal with Italian eye-frames manufacturer, Safilo. Not only was this true of Gucci, but this kind of licensing arrangement was common practice—the entire industry was structured this way…

Back in Silicon Valley, in May, 2014 Google Glass were first made available for purchase by the public through their Explorer Edition, setting off shockwaves in the tech industry that have compounded into the driving force for the largest R&D investment made across Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook, in their collective histories.

In September, 2014, Kering unveiled their plan to consolidate their brand stable’s eye-frames under their own umbrella. Not only did they launch a subsidiary, Kering Eyewear, and negotiate with Safilo a €90M payment to terminate their Gucci brand-license early, they also poached Safilo’s own CEO, Roberto Vedovotto, to build Kering’s new eyewear business unit. At that time Safilo was the second largest eye-frames company in the world (second only to Luxottica).

Kering’s move roiled the fashion world, resulting in an industry-wide realignment still reverberating through the global fashion and eye-frames industries to this day.

These two industries—tech and eyewear—have been moving headlong on a course of collision and convergence ever since. Probably the greatest misunderstanding about the emerging consumer smart glasses market is that this is a battle between Apple, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon (or insert your favorite indy, whether that be Vuzix, MagicLeap, etc.).

Premium eye-frames are a pre-existing $148B global market. The adjacent optometry industry is a $61B market. Completely apart from smart glasses, both are aggressively growing markets in their own right, and that’s without mentioning other adjacent industries like vision-care insurance.

If there is a battle at all, it could more accurately be framed as one between the tech industry as a whole, and the existing eye-frames and eye-care industries, because the decision in the minds of consumers will not be whether to purchase Apple glasses, or Google glasses, or Facebook glasses, or Amazon glasses, etc. The question will be, do they buy smart glasses at all, or do they continuing wearing their existing eye-frames, and sunglasses.

In March of 2014, Google announced that they would be launching versions of Glass in partnership with Luxottica, co-branded with two of their house brands: Ray-Ban, and Oakley. This co-branded product development was negotiated by then Luxottica CEO, Andrea Guerra.

In a story that first broke in the business section of Corriere della Sera, Italy’s leading newspaper, Luxottica’s founder and Chairman, Leonardo Del Vecchio, was alleged to have had a disagreement with Guerra over the Google contract, a decision some felt placed the reputations of two of Luxottica’s house brands at risk, through association with Glass—a product which by this time was experiencing substantial social backlash (wearers had by some acquired the unenviable moniker of “glassholes”). According to this version of the story, Del Vecchio wanted Luxottica to withdraw from the contract, while Google’s team steadfastly held Luxottica to the negotiated terms.

Del Vecchio contested this framing.

Guerra had been CEO of Luxottica for a decade at this time. He was not new in the role, and up to then his performance was widely praised—Luxottica’s market cap tripled under his tenure.

Nonetheless—whatever the source—the row between Guerra and Del Vecchio achieved operatic heights in the Italian trade press, reaching a crescendo on the first of September when Guerra’s termination was announced.

In spite of Guerra’s departure, the Google contract reportedly remained immovably in place, as Del Vecchio was quoted in the Wall Street Journal as being embarrassed by the scandal, having played out rather publicly. The business press was assured the Google contract would nonetheless be honored, and the story went away… yet no Luxottica / Google cobranded glasses under the Ray-Ban or Oakley labels ever shipped.

Further—now seven years later—Luxottica and Facebook are scheduled to ship consumer smart glasses, cobranded with the Ray-Ban label later this year. Now would be a good time to get to the bottom of whatever happened to the ill-fated Google / Luxottica partnership.

Apple is also preparing to launch a smart glasses product.

Four days after Guerra’s exit from Luxottica, news leaked that one time design director of Ikepod watches—famed Australian industrial designer, Marc Newson—had joined Apple. In another four days they would unveil the Apple Watch.

Peculiarly unmentioned in the tech-press coverage of the Apple Watch announcement was that Newson had also just launched another wearable accessory: a line of eye-frames for Luxottica competitor, Safilo. At this time Apple had already begun their streak of augmented reality related patent filings and acquisitions. What contact, if any, had Apple had with Safilo regarding smart glasses? Another reasonable question that no one in the tech press seemed interested in asking.

Given the loss of the Gucci contract (and their CEO), as well as the eminent expiration of Kering’s others brand licenses, any incoming CEO at Safilo would have an unenviable task upon arrival. The ever-so-recently renowned Italian eye-frames manufacturer was now maligned. An executive search for a qualified CEO would be difficult, unless they could find someone from within the firm to step up, and take the reins.

A recent Financial Times biography described Luisa Delgado’s career as a “mosaic.” The Swiss executive launched her career at the European arm of American consumer package goods giant, Procter & Gamble, eventually leveling-up to Managing Director of Nordic operations (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), before holding executive and/or board positions across a broad range of industries including Swedish furniture manufacturer, IKEA; German software firm, SAP; British investment bank, Barclays; and at this stage of our story, Safilo.

A recent Financial Times biography described Luisa Delgado’s career as a “mosaic.” The Swiss executive launched her career at the European arm of American consumer package goods giant, Procter & Gamble, eventually leveling-up to Managing Director of Nordic operations (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), before holding executive and/or board positions across a broad range of industries including Swedish furniture manufacturer, IKEA; German software firm, SAP; British investment bank, Barclays; and at this stage of our story, Safilo.

Stepping from her board director role into CEO, Delgado quickly looked to establish new brand license deals to offset the revenue loss from the Gucci exit. Other Kering brand departures would be imminent. New brand licenses would be needed, licenses not entangled with the large French fashion stables who had suddenly turned fickle—fickle not just at Kering, but now in a contagion extending to their largest rival LVMH, one for which Safilo also held prominent eye-frames licenses. The crown jewels of the LVMH stable—their Louis Vuitton namesake, as well as Dior—were both coming up for renewal.

Another puzzling mystery regards Safilo’s preexisting relationship with Marc Newson—what if any contact might Safilo have sought to established with Apple, regarding potential future smart glasses?

Before the end of this story, we’ll get to the bottom of this mystery, as well as the Google / Luxottica contract that never materialized… but for now we’ll wrap some needed context around the premium eye-frames industry.

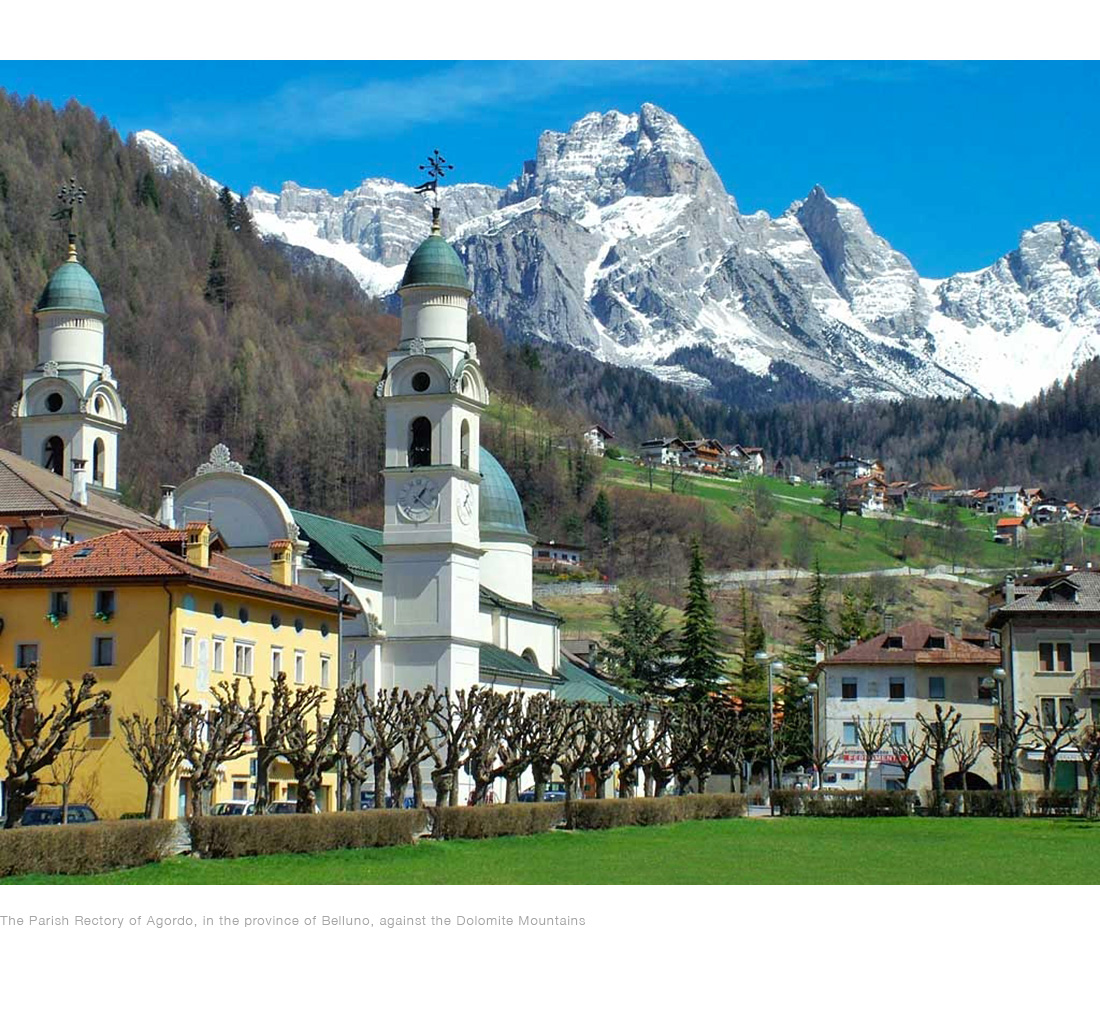

Leonardo Del Vecchio’s father died when he was five-months old, and his mother, destitute, turned him over to a Catholic orphanage at age seven. Raised by nuns, at fourteen the young Del Vecchio began an apprenticeship as a tool & die machinist at a factory in Milan, eventually earning enough to take evening classes in industrial design. With this experience, in his twenties he would relocate to the North Italian town of Agordo, in the province of Belluno.

Leonardo Del Vecchio’s father died when he was five-months old, and his mother, destitute, turned him over to a Catholic orphanage at age seven. Raised by nuns, at fourteen the young Del Vecchio began an apprenticeship as a tool & die machinist at a factory in Milan, eventually earning enough to take evening classes in industrial design. With this experience, in his twenties he would relocate to the North Italian town of Agordo, in the province of Belluno.

(He was not the only one.)

Agordo is a small factory town near the Austrian border. Even in the era of the youthful Del Vecchio, the mountainous region known as the Dolomites—part of the Italian Alps—was already home to Italy’s famed eye-frames industry. This was principally due to Safilo, then located in the Belluno municipality of Calalzo di Cadore. Safilo was established in 1934 when its own founder, Guglielmo Tabacchi (1900-1974) acquired Carniel, Italy’s “original” eye-frames factory (built in 1878). Other smaller optical companies built up around it. The region has a long history in spectacles.

Del Vecchio initially worked for hire as a component supplier to other frames companies, and in 1961 he named his studio Luxottica. He had a vision that eye-frames could be elevated to a high fashion accessory on par with designer shoes, or fine watches. He sold his first pair of frames under the Luxottica name in 1967, and by 1971 he introduced his first full eye-frames collection.

Just a few miles away from Del Vecchio, also in the province of Belluno, another young designer in Longarone named Giovanni “Nanni” Marcolin would launch his eponymously branded Marcolin Eyewear—like Del Vecchio’s Luxottica studio—also in 1961.

The municipality of Limana, also in Belluno, is the home of De Rigo, the smallest and youngest of the “big four” Italian frames houses. It was founded first as Charme Lunettes by brothers Ennio and Walter De Rigo. Soon after, the brothers would acquire the brand right to “Lozza,” the namesake label of Carniel’s founder, Giovanni Lozza, giving both Di Rego and Safilo competing claims of heritage to Italy’s oldest eye-frames manufacturer.

The globally dominant, Italian eye-frames industry is comprised principally of these four companies (as well as a fifth American owned company, Marchon, that manufactures in Italy, that we’ll get to in time).

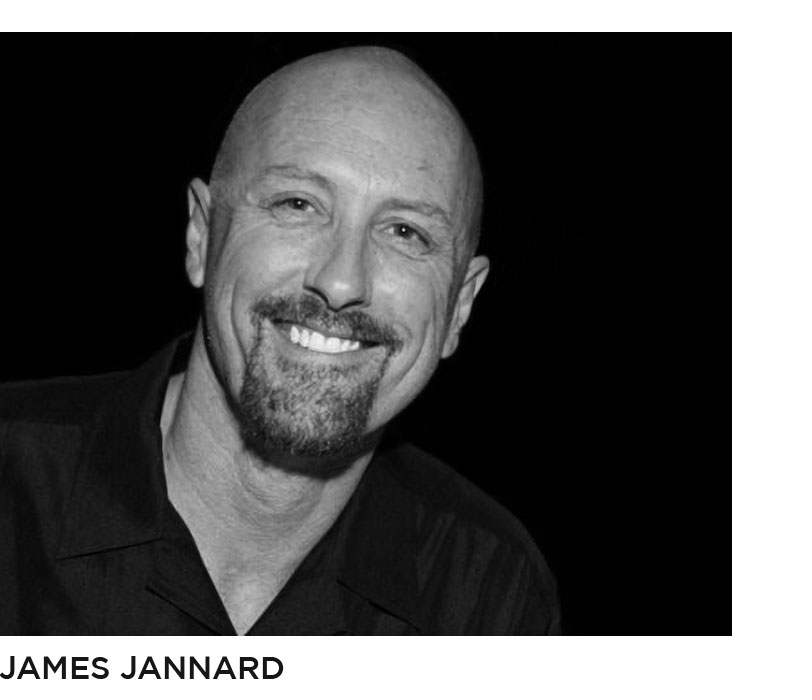

Also in the 70s, an American entrepreneur named Jim Jannard launched Oakley as a BMX and motocross sports apparel and accessories company. While his first hit product were “Oakley Grips,” for motorcycle handlebars, by the 1980s his stylized eye-frames had become their high-margin hit product, so much so that he discontinued motocross parts, and pivoted the company to apparel, leading with eyewear. Jannard and Del Vecchio’s paths would soon collide.

Also in the 70s, an American entrepreneur named Jim Jannard launched Oakley as a BMX and motocross sports apparel and accessories company. While his first hit product were “Oakley Grips,” for motorcycle handlebars, by the 1980s his stylized eye-frames had become their high-margin hit product, so much so that he discontinued motocross parts, and pivoted the company to apparel, leading with eyewear. Jannard and Del Vecchio’s paths would soon collide.

In the ensuing decades, Del Vecchio earned for himself a reputation as a visionary entrepreneur of ruthless ambition, growing Luxottica into an international juggernaut, and with an estimated personal net worth of just over $30B, becoming the wealthiest man in Italy, in the process.

Let’s take a closer look at the company Del Vecchio built.

A milestone in Luxottica’s history was partnering with famed Italian fashion house, Giorgio Armani. In 1988 Luxottica signed a brand license deal to manufacture and sell fashion eye-frames under the Armani name, establishing the fashion brand licensing strategy that they would master, and which would become the norm throughout the eye-frames industry.

In 1990 Del Vecchio took the company public, listing on the New York Stock Exchange. The 90s would see fabulous growth, largely through acquisition.

Corporate raider style, in 1995 Luxottica successfully staged a hostile takeover of United Shoe Corp. If this seems an odd target, United had diversified out of shoes. Luxottica’s goal was to get control of United’s wholly-owned subsidiary, LensCrafters.

As Del Vecchio’s reputation as a cutthroat businessman grew, his two most infamous acquisitions were yet to come.

In 1999 Luxottica acquired Bausch & Lomb’s eye-frames business, the gem of the deal being Ray-Ban, America’s number-one selling sunglasses (It also came with the lesser known Revo brand, which Luxottica would sell-off in 2013).

Ray-Bans were effectively removed from the market, manufacturing relocated to Italy with state-of-the-art tooling and improved materials, the new Ray-Bans were brought up to Luxottica’s build quality. With the sales channel constricted, and inventory depleted, Luxottica relaunched Ray-Ban in 2004.

A pair of classic Wayfarers now retail for over $150.

While Bausch & Lomb exited the eye-frames market voluntarily, to focus on their contact lens business, not all brands succumbed to Del Vecchio’s will so gracefully.

Throughout the 90s, Oakley butted heads with many competitors, mostly over allegations of infringing on their design and engineering patents. Among others, Bausch & Lomb stood accused of making Oakley knockoffs, against which Oakley won a landmark case in 1995.

Jannard hired Scott Olivet—a former Nike VP over subsidiary brands. Interesting choice as Jannard had also fought a nearly five year long legal battle with Nike, with dueling counter claims of design infringements. Jannard had successfully leveraged IP to protect his market position in the past. He could be pretty ruthless himself.

With PearlVision, LensCrafters, Sunglass Hut, Target, and Sears points of sales all under Luxottica’s control, they could now effectively rattle Oakley’s stock price at any time by adjusting their volume of Oakley inventory.

Jannard, a billionaire, had much of his net worth tied up in Oakley shares (though publicly traded, he owned 68%). Any stock price slide placed Jannard’s own fortune at risk. He succumbed, and Scott Olivet negotiated Oakley’s sale to Luxottica. Jannard’s battle with Del Vecchio finally came to an end in 2007.

By this point in Luxottica’s rise they had begun to draw accusations of anti-competitive behavior from both the media and ambitious political figures, including then New York State Attorney General, Eliot Spitzer who launched a 2003 antitrust investigation into Luxottica’s business (it went nowhere); and nearly a decade later 60 Minutes, produced a 2012 exposé… also resulting in nothing.

Not only had Del Vecchio established himself as a competitor to be reckoned with, but also an untouchable Teflon Don. Business was good (and still is).

In January 2017, Del Vecchio bested even himself.

The Luxottica / Essilor merger was technically an acquisition. Essilor acquired Luxottica for $24B. One could be forgiven for thinking it were the other way around. In a post acquisition analysis, industry trade publication, Business of Fashion noted two developments driving the merger: the shakeup in the eye-frames brand-licensing model triggered by Kering, and the emerging consumer smart glasses market.

This would be a good time to take inventory of Luxottica & Essilor’s combined holdings. Essilor has a dominant (but not majority) position in the global corrective lens market.

While their core business focuses on corrective lens manufacturing, Essilor also entered the eye-frames market by acquiring FGX International in 2009. This included their name-sake Foster Grant eye-frames brand, a portfolio of licensed brands, as well as their extensive non-prescription “reading glasses” business. Foster Grant itself did not directly compete with Luxottica. They cornered a lower end of the market. Foster Grant frames and glasses can be found in sales channels like Walgreens and other pharmacies, at substantially lower price points.

Essilor brought other significant sales channels into the fold with both FramesDirect, then the leading online eye-frames retailer; as well as Vision Source, the U.S.’ largest eye-care franchise (and largest retailer, overall in the U.S. market).

Not all of their revenue are frames and corrective lenses.

Essilor is also a leading manufacturer of ophthalmic equipment. Because few of the manufacturers in the medical equipment space are exclusive to vision equipment, divvying up who controls how much market share is not easily sussed out. One industry report noted Essilor as the second largest player in the space behind Alcon, but ahead of Johnson & Johnson; however of those, only Alcon’s Annual Report separated out revenue from such equipment… and even there lumps it together as “Equipment/Other” at 16% of their $7.4B in 2019 sales (where possible I’ve tried to avoid referencing 2020 reports, as the pandemic threw numbers into disarray). Johnson & Johnson doesn’t distinguish vision equipment revenue from other medical devices, and so on, down the list. Nonetheless the combined EssilorLuxottica is a major player in the medical vision-equipment space.

Essilor is also a leading manufacturer of ophthalmic equipment. Because few of the manufacturers in the medical equipment space are exclusive to vision equipment, divvying up who controls how much market share is not easily sussed out. One industry report noted Essilor as the second largest player in the space behind Alcon, but ahead of Johnson & Johnson; however of those, only Alcon’s Annual Report separated out revenue from such equipment… and even there lumps it together as “Equipment/Other” at 16% of their $7.4B in 2019 sales (where possible I’ve tried to avoid referencing 2020 reports, as the pandemic threw numbers into disarray). Johnson & Johnson doesn’t distinguish vision equipment revenue from other medical devices, and so on, down the list. Nonetheless the combined EssilorLuxottica is a major player in the medical vision-equipment space.

Essilor also has a substantial IP portfolio including waveguides and other near-eye display technology. While Silicon Valley tech giants have vast troves of IP across all aspects of a smart glasses product, Essilor’s patent portfolio (specific to smart glasses) is more narrow—focused in optics, but it is noteworthy. Essilor does not have a large startup investment portfolio, but one investment that’s currently having a moment is DeepOptics, which spent years developing digital adaptive focus lenses, around which they currently have a Kickstarter to productize their adaptive focus technology into a pair of smart consumer sunglasses.

Essilor also has a substantial IP portfolio including waveguides and other near-eye display technology. While Silicon Valley tech giants have vast troves of IP across all aspects of a smart glasses product, Essilor’s patent portfolio (specific to smart glasses) is more narrow—focused in optics, but it is noteworthy. Essilor does not have a large startup investment portfolio, but one investment that’s currently having a moment is DeepOptics, which spent years developing digital adaptive focus lenses, around which they currently have a Kickstarter to productize their adaptive focus technology into a pair of smart consumer sunglasses.

While Essilor includes contact lenses among their product offerings, in a market dominated by companies like Bausch+Lomb, Alcon, Johnson & Johnson, and CooperVision, Essilor is not a leading player in contacts.

The combined manufacturing footprint of Luxottica and Essilor is both international, and staggering. Essilor has 27 international plants for fabricating prescription lenses, three more for photochromic (transition) lenses, and an additional three for sunglass lenses, with plants located on almost every inhabited continent except Australia. They then move the rough lenses through a network of 449 finishing laboratories around the world servicing regional retail, that mill and polish each pair of lenses to fulfill local prescription orders, and cut them to fit the desired frames.